By: Luther Kovac: Recently I have experienced a disturbing series of events, all occurring within a very short time of one another. Several unexpected deaths early this year had already contributed to a melancholy tone that permeated my everyday life. Then other things began to happen. New procedures at my place of business have caused a disruption to my sleeping patters and morning routines. My mechanic of over 10 years has suddenly closed shop, his signs removed and gates locked, and all signs that he had ever been there simply gone. The next day the door to my favorite diner was locked. I looked into the window and all appeared normal except it was empty with the lights off; then I spotted the signs advertising the new Spanish restaurant that will be replacing it. My heart was pounding. Like an animal whose steady routines were suddenly altered I tensed and froze and stared at the offending disruption. I suddenly had the urge to keep moving, to be somewhere that I was anonymous and invisible to all, somewhere safe. Of course, there was no safe place to go, because the adversary I sought to avoid was entropy, change, or as the voice in the back of my mind was whispering, Loki. I had the uneasy feeling that my life was, once again, going to become interesting, and how I felt about that would not matter in the least. On the other hand, how I dealt with it was going to determine my Wyrd (future) for some time to come. It has always been my opinion that Western monotheism tends to oversimplify morality, portray their divine entities as extremes, and pushes everyone to choose a side in any conflict. So it is not surprising that, with today’s Judeo-Christian perspectives, Loki has been portrayed as the pagan Norse equivalent to the Christian Devil. It is undeniable that Loki shares some of the Devil’s characteristics, such as a selfish nature and a penchant for betrayal, but his place in the old religion was much more complex. Loki is the Norse variant of the trickster god, and is considered by many to be an important and necessary agent of change. His sphere of influence touches on the chaos behind reality, he is a reminder that things are not always as they seem, and that unexpected events can have world changing consequences. However, it is not my intention to rehabilitate Loki or portray him as neutral; his association with the Devil may be oversimplified but it is not unfair. Loki has worked for and against the gods, but can be malicious and spiteful, and overall he is far more harmful than benevolent. He is not simply an outside player with his own agenda, he is the catalyst for Ragnarok. Because of his treachery he is something less than neutral, but can inspire us to wisdom in ways the other gods do not. The lessons of Loki are painful, and once learned are not easily forgotten.

“As Loki was the embodiment of evil in the minds of the Northern races, they felt nothing but fear of him, built no temples in his honor, offered no sacrifices to him, and designated the most noxious weeds by his name. The quivering, overheated atmosphere of summer was also supposed to betoken his presence, for the people were then wont to remark that Loki was sowing his oats, and when the sun drew water they said Loki was drinking.”

-Myths of the Northern Lands, by H.A. Guerber p. 200

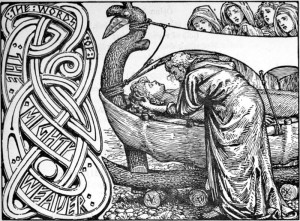

Knowing Loki’s nature does not help us avoid his influence; it might be overcome but never avoided, not even by Odin. The reason for this is because, among other things, Loki is the personification of change. When the Norns weave the threads of Wyrd (destiny) they cross and re-cross, each affecting the others in accordance with Orlog, the universal law of Nature and the Universe. Occasionally the Norn goddess Skuld will shred the weave and the future will be remade according to the same law, but in a different pattern. This sudden alteration in the threads corresponds to Loki’s role in our lore. He is upheaval, the unpredictable variable, the freak accident, and the unexpected opportunity. He is change, and cannot be ignored. Understanding change as a concept will at least partially explain Loki’s role in Norse/Teutonic religion. Many say that change is necessary, but is it necessary or inevitable? The difference is important. Some people will welcome the unstoppable because they have no control over it, and seek legitimacy in its power even as it overwhelms them. Whenever I hear someone say “change is good” I usually find that they cannot easily explain why a particular change would be, so they generalize instead. Not all change is good, as any honest assessment will show, and change for the sake of change is chaos. Sometimes change seems to occur in cycles, like so many other things, and during those times one wonders what will happen next. People say that good things can happen alongside bad ones, and while that is not always true, it is true often enough to be noticed. Change causes both obstacles and opportunities for us, but it rarely gives us exactly what we want; we have to work for that. Obstacles need to be overcome, and opportunities recognized, seized and their gains protected. Life is not supposed to be easy, a point that is often reflected in the Old Religion. Because of the recent cycle of change I am experiencing, and the advice of a friend, I decided to look for the possibility of something positive in the recent upheaval and I found it. Weeks ago I received a promotion from my employer and I just found out that an extended family member is expecting a child (making me happy indeed). Also, looking at the lives of those around me showed that I was not alone. I began writing this article because of personal experiences and as I finish it I find that this season of change has seriously impacted many of the people I know. It is tempting to believe that every negative change is balanced by something good, but that notion is deceptive. The more changes that occur the more likely you can benefit from some of them, but balancing what is bad and good is not a function of chaos even if it sometimes seems that way. For example; during a war, if both sides are mutually annihilated, you could say that the outcome was balanced, but that result would be considered bad for both sides involved. Balance, and what we consider good or bad, is subjective. The same event that benefits you might be very bad for someone else. Much of our ancient lore was lost, but Loki (true to form) is considered a great riddle by those studying ancient Teutonic religion. Loki is clearly missing from the religion of most Germanic peoples, but his role among the Scandinavians was extremely significant. My intent is to provide a brief overview of Loki to help illustrate his place in the Old Religion, and how it manifests in our lives. Our ancestors did not have a static belief system. Events in ages past have caused both divergence and fusion of local lore, and the deeper one digs into our past the more fragmented and varied the lore can become. Loki is the son of the giant Fárbauti and Laufey, and blood-brother to Odin, but some of our ancestors saw him as the equivalent of Ve, one of Odin’s two birth brothers, and called him Lodur (Guerber p19). He is considered a giant or a fire god, but exactly what the difference was between giants and gods is ambiguous; for example, Odin’s mother Bestla was a giant. Loki was married to the goddess Sigyn but sired three monstrous offspring by the giantess Angrboda; the giant wolf Fenris, Jormungand (the Midgard serpent), and Hel (the goddess of disease and the underworld). These three entities, along with Fenris’ own offspring Sköll and Hati, are to side with Loki and the Jotun (giants) against the gods at Ragnarok. Loki was a shape-shifter and sometimes appeared as a female. One of his many escapades, where he took the form of a mare, resulted in his giving birth to Odin’s eight legged steed Sleipnir. One characteristic of his adventures was that he was often both the cause of, and the solution to, a problem. His actions against Odin’s son Baldr went beyond mischief, Loki’s intentions were fueled by envy and manifested as pure malice.

“The death of Baldr inflicts great loss and injury on the company of the gods, and thus forms the ominous prelude to the impending destruction of the world. It was this latter aspect in which the myth was viewed on that boundary line of the pagan and Christian ages in which Völuspa was composed.”

–Religion of the Teutons, by Chantepie De La Saussaye, p.257

Baldr was the son of Odin and Frigg. He was the god of beauty, of light and summer. He was the embodiment of moral purity and innocence, and was thought to be universally loved. Baldr was disturbed by dreams that he could not recall, and the other gods noticed his uncharacteristic lack of cheer. The giants said that his dreams were an omen of ill fortune that would befall him, which was true (we assume that even the Jotun held Baldr in high regard).

“Frigg, subsequent to Baldr’s evil dreams, had put all objects under oath not to harm Baldr. On the thing the gods, certain not to hurt him, began in jest to throw and shoot all kinds of missiles at Baldr; nothing could hit him. Now Loki had learned from Frigg that the insignificant mistletoe (mistilteinn) had not been put under oath, and he now put this mistletoe as an arrow in the hand of the blind Hodhr, who shot Baldr dead with it. All the gods wept, but to no avail.”… “The Æsirthereupon send Hermodr, the son of Odhin, to Hel, and he returns with the promise that Baldr shall return in case all objects, animate and inanimate, weep for him. The Æsir prevail upon all objects to do so; the tears are universal. Thokt alone, the giantess of the cave in the rocks, – Loki in disguise, – will not weep and thus prevents the return of the god. She says: ‘Neither living nor dead was he of any use to me. Let Hel hold what it has.’”

-Religion of the Teutons, by Chantepie De La Saussaye, p. 256

It is clear that Loki’s actions culminate in catastrophic consequences. What is less obvious is the wisdom that can be gained from a deeper study of the dynamics involved. Although the gods are not above deception when necessary, they seem to prefer to deal with problems directly when possible. This is seen by their worshipers as a positive trait, and it can be, but it can also lead to flaws which can be taken advantage of as Loki so often demonstrates. Trying to make Baldur invulnerable was a reasonable precaution, but flaunting his protection by making a game of striking him with deadly weapons was hubris. It would not have taken much effort to get the oath from mistletoe; the plant loved Baldr as much as anything else did. Ignoring mistletoe because of its apparent insignificance may have seemed like a minor detail, but if someone was specifically looking for a weak point to exploit it would be giving them everything they needed, especially if you discussed it with people that didn’t need to know, as Frigg did. The gods did not expect the level of creativity and planning that went into the attack because it was not the way they would have gone about it. Not everyone thinks as we do or approaches problems in the same way, so it is wise to consider how others see things and what they might be capable of. Loki even manipulated one of the gods to strike the killing blow, which might have been necessary if we assume that he also swore the oath not to harm Baldr (technically he may have needed someone else to throw the mistletoe). Loki’s skill and subterfuge was more than a match for the strength of all of Asgard combined. Like men, the gods saw what they expected to see, and Loki manipulated those expectations like a puppeteer. The death of Baldr shows us that there are more ways to victory than the direct route, and cunning counts for much against a strong opponent, or for that matter, against any opponent.

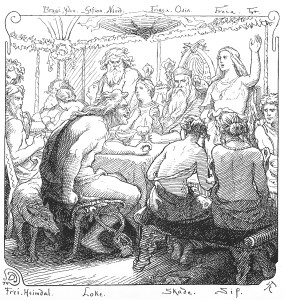

The gods continued to tolerate Loki because they did not realize that he was ultimately responsible for the death of Odin’s son. Loki’s lack of grief for Baldr did cast suspicion on him, and because of this he was no longer welcome in the halls of Asgard. Escaping retribution was not enough for Loki, he continued to make trouble and began to openly slander the gods until they finally punished him. Loki pushed his way into the feast hall of Ægir and slew Fimafeng, the guard at the door, either because he feels slighted by him or because he is jealous of the praise Fimafeng was receiving. Loki flees after the act, but to everyone’s astonishment he returns later and demands a seat at the table. The gods are ready to kill him, but Loki uses past oaths and the rules of hospitality to gain a seat. He proceeds to insult each god and goddess in turn, bringing up embarrassing things or fabricating them if necessary. He accuses each goddess of a wanton lust for men and unfaithfulness to their husbands. The other gods say he is drunk and should leave, but he continues to disparage them instead. He admits to Frigg that he was responsible for her son’s death, sealing their will to punish him, but Loki knows that they do not want blood spilled in their hall and continues his abuse. Only when Thor threatens him does he relent and leave. Loki said it was because he knew Thor would truly attack him, which can also be taken as an insult because it meant that Thor would be so uncouth as to spill blood in the feast hall. Loki escapes but eventually is captured by the gods.

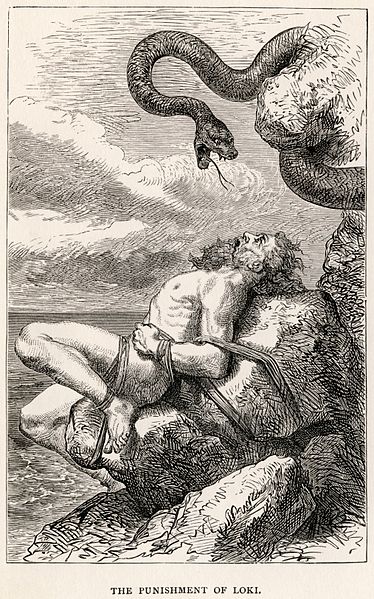

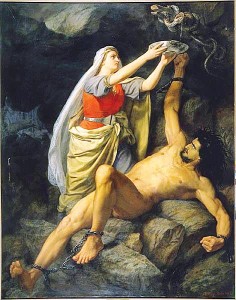

“In Lokasenna Loki reviles all the gods and goddesses at the feast of Ægir, and yields to Thor alone. He is captured and chained, and Skadhi fastens a snake above him, whose venom drips down upon his face. Loki’s wife, Sigyn, contrives to catch the venom in a vessel, and only when this vessel becomes full and has to be emptied does a drop fall upon Loki, whose frightful convulsions then cause the earth to quake.”

-Religion of the Teutons, by Chantepie De La Saussaye, p. 264

Loki’s original act against Baldr (though devastating) seems in character with his previous exploits, but instead of becoming part of the solution this time he continues to frustrate the gods to ensure that Baldr remains dead. In the past Loki appears to be motivated not just by whim, but by self-interest, even when he is fixing a problem. Loki could have influenced his daughter Hel to release Baldr from the underworld, but he did not. He could have gone along with Hel’s requirements to bring Baldr back, but instead purposely caused the gods efforts to fail. It was not in Loki’s self-interest to continue to act against Baldr, and the will of Odin, while the gods tried to undo what happened, but Loki seemed to be motivated by spite. Spitefulness, vengeance and related emotions have their place in the Old Religion, and were not automatically dismissed as wrong by our ancestors; in fact, vengeance was often portrayed as something positive. The self-defeating mistake in Loki’s actions was that instead of contributing to his greater goals (which usually including his own preservation), his spite and viciousness became the goal themselves. The result no longer served practical self-interest or a greater strategy, and caused the instigator to lose control of the situation. It is noteworthy that what ultimately caused the gods to turn on Loki was not his deceptions or poor character, but his uncharacteristic openness about how he felt about them, and his blatant confession of his role in Baldr’s death. Had he continued his normal pattern of behavior they might not have figured out his betrayal. Guile and deception are weapons as swords or spears, even Odin was known to travel in disguise if it served his purpose. Whether or not deception is wrong depends on who you’re working for and what your goals are. Like many concepts, it all depends on the angle you look at it. With this in mind, Loki’s deceptiveness might be distasteful but it is not what makes him so dangerous. It is what he uses it for that is the problem. Loki killed the embodiment of all that was good. He murdered beauty. He took away someone that everyone and everything loved. When Loki’s binds are broken, he and his offspring revolt against the gods and cause the destruction of everything. During Ragnarok, the final battle, the gods and their enemies slaughter one other, the sun is extinguished, and the world burns. Loki is not just a trickster, he is the betrayer, and the hand of extinction.

“The Ship of Death is sailing over the sea. On board are the sons of Muspel, who were bound; the stricken Jotuns; freed from bonds; Garm, the watch-dog; and the unfettered wolf Fenrer. Monsters gaunt and grim are in the ship, and Hel is there also. Loke is the pilot and holds the rudder. To Ironwood he steers; over it his host he shall lead to the plain of Vigrid.”… “From the south comes black Surtur. In his hand flames the Sword of Victory, which he hath received from Suttung. Seething fire gleams from the sunbright blade, and his bleak avengers follow him.”

–Teutonic Myth and Legend, by D.A. Mackenzie, p. 180

“In Heaven there is disaster. Closer and closer hath the giant wolf Skoll crept towards the sun, and now he swallows it. By Hati-Managarm is the moon devoured.” “So is the sun darkened at high noon, the heavens and earth are turned red with blood, the seats of the mighty gods drip gore. So is the moon lost in blackness, while the stars vanish from the skies.” “Now Surtur completes creation’s doom. He casts his firebrand against the scattered Asa-hosts, and those who remain are burned up, save Vale and Vidar sons of Odin, and Modi and Magni sons of Thor. Midgard is swept by flame, the smoke curls round mountain tops; all things are burned up; nothing with life remains”… “Earth, smouldering and black, sinks into Ocean; the billows cover it.” “Now there is naught but thick blackness and silence unbroken. The end hath come – Ragnarok, ‘The Dusk of the Gods’!”

–Teutonic Myth and Legend, by D.A. Mackenzie, p. 181

One important perspective in Norse/Teutonic religion that differs from many others is that the End Times it is not about good triumphing over evil. Our ancestors that followed Odin’s way were more practical minded than that. They understood that moral superiority and victory were independent concepts; their gods were not perfect, and at least some of the giants had legitimate grievances against them. Loki was the catalyst for the death of the much of the universe, but it was the gods own mistakes tipped the balance against them in the final battle. However, perhaps Odin, in his wisdom, saw further than the Eddas recount and took all into consideration factors unknown to us, because the darkness following Ragnarok is not the end. A few gods remain, Baldr returns, and the land eventually rises from the sea. Before being swallowed the sun gave birth to a daughter that follows her old path. There is light again and life begins anew, and the Eddas describe the rebirth of mankind.

“In the place called Hoddmímir’s Holt there shall lie hidden during the Fire of Surtr two of mankind, who are called thus: Líf and Lífthrasir, and for food they shall have the morning-dews. From these folk shall come so numerous an offspring that all the world shall be peopled… ”

–Prose Edda by Snorri Sturlson, translation by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur, p. 83

What of the Germanic tribes where Loki seemed to be missing? He may not actually be missing, but dispersed. Some believe that Loki is an aspect of Odin, a “dark side” that the Norse separated and gave a persona of its own. Odin’s nature is not simple. The Allfather is spirit and wisdom; he employs deception and misdirection; he is the keeper of secrets and is not above manipulation to achieve his goals. He shares many of Loki’s characteristics but utilizes them for different purposes. Concepts connected to Loki can also be found elsewhere in our lore. Loki and many of the characteristics associated with him are connected to the Kenaz rune of the Elder Futhark (also known as the torch rune).

“This is the rune of creativity – or more accurately, in Germanic terms, of the ability to shape. This is symbolized by controlled fire – the torch – but also by the fires of the hearth, harrow (= altar), forge, and pyre. Each serves the human will to shape or reshape itself or its environment. In a person this is the bright light that all recognize as “charisma.” Although this is ever present within the runester, it is most awake in “working states,” that is, when inspiration is high but physical activity is restive.” “Kenaz is the root of all technological knowledge, the rune of the craftsman and the crafty one – Wayand (ON Volundr) and Loki. It is also the mystery of the deep connection between sexuality and creativity that is so characteristic of the Odhinic path.” “The hidden root concept behind kenaz is dissolution, whether by organic means (see the Norse rune name kaun [ulcer, sore]) or by fire (torch). This dissolution is necessary for reshaping to take place in accordance with a willed plan.”

–Runelore, by Ered Thorsson, p. 119

Many of the Loki’s characteristics are shared by other entities. Odin often appears in disguise, and gathers information from the unsuspecting. The destructive potential of fire is seen in Surt (the fire giant). Creativity/craftsmanship are also associated with giant Thjasse and especially the elf prince Volund (or Wayand Smith), who also represents resistance, ruthlessness and vengeance. As a shapeshifter, Loki also signifies rapid adaptation to changing circumstances, a very special type of innovation. One does not have to admire Loki in order to appreciate his intelligence, creativity and resourcefulness, or to embrace the potential of the torch rune. Although Loki is prominent in Norse lore, he did not have worshippers, and so far I haven’t found any credible historians or archaeologists who claim differently. There are some modern religious authorities that say he is essential to completing the balance and cycles contained in Norse religion, and that is certainly true; but others go so far as to claim that modern pagans who refuse to worship or invoke Loki lack a deeper understanding of our lore. I find their logic difficult to accept. I seek the wisdom of our ancestors, and they did not worship Loki; I’m confident that our ancestors had a deeper understanding of their religion than we do today. Their approach to him still seems sensible; worshiping Loki as we know him from the Eddas is tantamount to worshiping chaos, and welcoming extinction. Invoking Loki directly is to court danger and uncertainty with only a faint hope that an opportunity might arise from it. Better to focus on the kenaz rune, and use innovation and resourcefulness to come up with your own course of action. Loki is an agent of change, but one does not worship change. We learn from it, adapt to it, and survive it. by Luther Kovac References: Religion of the Teutons, by Chantepie De La Saussaye Teutonic Myth and Legend, by D.A. Mackenzie Myths of the Northern Lands, by H.A. Guerber Teutonic Mythology, by Viktor Rydberg Poetic Edda, Bellows translation Prose Edda, by Snorri Sturlson, translation by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur Runelore, by Ered Thorsson